Navigating Files and Directories¶

whoami¶

When you log on you will see a prompt that looks something like:

nbuser@nbserver:~$

On some systems the first part of this will be your username as your username, but we are running in the notebooks terminal which has created a special user for us nbuser and the terminal session is running on a server called nbserver. Type the command whoami, then press the Enter key (sometimes marked Return) to send the command to the shell. The command’s output is the ID of the current user, i.e., it shows us who the shell thinks we are:

%%bash2 --dir ~

whoami

More specifically, when we type whoami the shell:

- finds a program called whoami,

- runs that program,

- displays that program’s output, then

- displays a new prompt to tell us that it’s ready for more commands.

In this lesson, we have used the username nbuser or nelle (associated with our hypothetical scientist Nelle) in example input and output throughout.

However, when you type this lesson’s commands on your computer or another system, you could see and use something different, namely, the username associated with the user account on your computer. This username will be the output from whoami. On other systems, in what follows, nbuser or nelle should always be replaced by that username.

The linux file system¶

The part of the operating system responsible for managing files and directories is called the file system. It organizes our data into files, which hold information, and directories (also called "folders"), which hold files or other directories.

Several commands are frequently used to create, inspect, rename, and delete files and directories. To start exploring them, we'll go to our open shell window.

First let's find out where we are by running a command called pwd (which stands for "print working directory"). Directories are like places - at any time while we are using the shell we are in exactly one place, called our current working directory. Commands mostly read and write files in the current(present) working directory, i.e. "here", so knowing where you are before running a command is important. pwd shows you where you are:

%%bash2

pwd

Here, the computer's response is as above, which the data-shell directory we extracted on the schedule page.

To understand what a "home directory" is, let's have a look at how the file system as a whole is organized. For the sake of this example, we'll be illustrating the filesystem on our scientist Nelle's computer. After this illustration, you'll be learning commands to explore your own filesystem, which will be constructed in a similar way, but not be exactly identical.

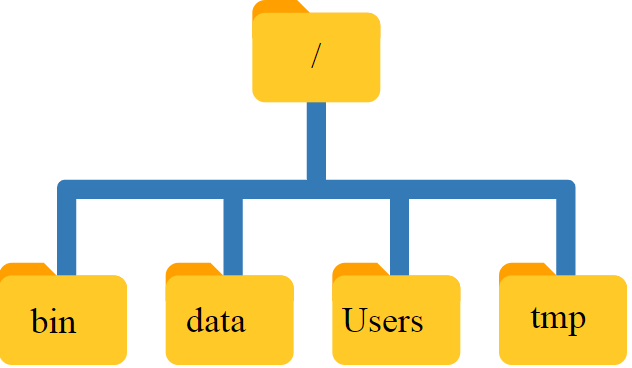

On Nelle's computer, the filesystem looks like this:

At the top is the root directory that holds everything else. We refer to it using a slash character, /, on its own; this is the leading slash in /Users/nelle.

Inside that directory are several other directories: bin (which is where some built-in programs are stored), data (for miscellaneous data files), Users (where users' personal directories are located), tmp (for temporary files that don't need to be stored long-term), and so on.

We know that our current working directory /Users/nelle is stored inside /Users because /Users is the first part of its name. Similarly, we know that /Users is stored inside the root directory / because its name begins with /.

Underneath /Users, we find one directory for each user with an account on Nelle's machine, her colleagues the Mummy and Wolfman.

The Mummy's files are stored in /Users/imhotep, Wolfman's in /Users/larry, and Nelle's in Users/nelle. Because Nelle is the user in our examples here, this is why we get /Users/nelle as our home directory.

Typically, when you open a new command prompt you will be in your home directory to start.

Now let's learn the command that will let us see the contents of our own filesystem. We can see what's in the data-shell directory by running ls, which stands for "listing":

%%bash2

ls

ls prints the names of the files and directories in the current directory. We can make its output more comprehensible by using the flag -F (also known as a switch or an option) , which tells ls to add a marker to file and directory names to indicate what they are. A trailing / indicates that this is a directory. Depending on your settings, it might also use colors to indicate whether each entry is a file or directory.

%%bash2

ls -F

Getting help¶

ls has lots of other flags. There are two common ways to find out how to use a command and what flags it accepts:

- We can pass a

--helpflag to the command, such as:ls --help - We can read its manual with man, such as:

man -ls

Depending on your environment you might find that only one of these works (either man or --help). We'll describe both ways below.

The --help flag¶

Many bash commands, and programs that people have written that can be run from within bash, support a --help flag to display more information on how to use the command or program.

%%bash2

ls --help

%%bash2

ls -j

The man command¶

The other way to learn about ls is to type

%%bash2

man ls

This will turn your terminal into a page with a description of the ls command and its options and, if you're lucky, some examples of how to use it.

To navigate through the man pages, you may use ↑ and ↓ to move line-by-line, or try B and Spacebar to skip up and down by a full page. To search for a character or word in the man pages, use / followed by the character or word you are searching for.

To quit the man pages, press Q.

The data¶

For the rest of this lesson we will make use of a collection of files that are in a zip file that we copied to our home direectory in the setup.

%%bash2

ls -l intro-linux

We need change our location to a different directory, so we are no longer located in our home directory.

The command to change locations is cd followed by a directory name to change our working directory. cd stands for “change directory”, which is a bit misleading: the command doesn’t change the directory, it changes the shell’s idea of what directory we are in.

Let’s say we want to move to the directory we just created. We can use the following series of commands to get there:

%%bash2

cd intro-linux

Now our directory contains a zip file, data-shell.zip, (how can you check this?) which we need to unzip with the command:

%%bash2

unzip data-shell.zip

Now we can check the contents of the zip by running ls:

%%bash2

ls

Unzipping the file has created a new directory data-shell. As before we can check the contents of this with:

%%bash2

ls -F data-shell

Here, we can see that our data-shell directory contains mostly sub-directories. Any names in your output that don't have trailing slashes, are plain old files. And note that there is a space between ls and -F: without it, the shell thinks we're trying to run a command called ls-F, which doesn't exist.

We can also use ls to see the contents of a different directory. Let's take a look at our data directory by running ls -F data, i.e., the command ls with the -F flag and the argument data-shell. The argument data tells ls that we want a listing of something other than our current working directory:

%%bash2

ls -F data-shell

Your output should be a list of all the files in the data-shell directory. This is the directory that you downloaded and extracted at the start of the lesson. If the directory does not exist, check that you have downloaded it to the correct folder.

As you may now see, using a bash shell is strongly dependent on the idea that your files are organized in a hierarchical file system. Organizing things hierarchically in this way helps us keep track of our work: it’s possible to put hundreds of files in our home directory, just as it’s possible to pile hundreds of printed papers on our desk, but it’s a self-defeating strategy.

Let's say we want to move to the data directory we saw above. We can use the following commands to get there:

%%bash2

cd data-shell

cd data

These commands will move us from our home directory to the data-shell directory and then into the data directory. cd doesn't print anything, but if we run pwd after it, we can see that we are now in /Users/nelle/Desktop/data-shell/data. If we run ls without arguments now, it lists the contents of /Users/nelle/Desktop/data-shell/data, because that's where we now are:

%%bash2

pwd

%%bash2

ls -F

We can do this again and change directory into the elements directory and use pwd to verify that we have changed into another directory.

%%bash2

cd elements

pwd

We now know how to go down the directory tree, but how do we go up? We might try the following:

%%bash2

cd data

But we get an error! Why is this?

With our methods so far, cd can only see sub-directories inside your current directory. There are different ways to see directories above your current location; we'll start with the simplest.

There is a shortcut in the shell to move up one directory level that looks like this:

%%bash2

cd ..

.. is a special directory name meaning "the directory containing this one", or more succinctly, the parent of the current directory. Sure enough, if we run pwd after running cd .., we're back in /Users/nelle/Desktop/data-shell/data:

%%bash2

pwd

The special directory .. doesn't usually show up when we run ls. If we want to display it, we can give ls the -a flag:

%%bash2

ls -F -a

-a stands for "show all"; it forces ls to show us file and directory names that begin with ., such as .. (which, if we're in /Users/nelle, refers to the /Users directory) As you can see, it also displays another special directory that's just called ., which means "the current working directory". It may seem redundant to have a name for it, but we'll see some uses for it soon.

Note that in most command line tools, multiple flags can be combined with a single - and no spaces between the flags: ls -F -a is equivalent to ls -Fa.

We can get back to the data-shell directory the same way:

%%bash2

cd ..

pwd

Let's try returning to the elements directory in the data direcotry, which we saw above. Last time, we used two commands, but we can actually string together the list of directories to move to elements in one step:

%%bash2

cd data/elements

Check that we've moved to the right place by running pwd and ls -F

If we want to move up one level from the data directory, we could use cd ... But there is another way to move to any directory, regardless of your current location.

So far, when specifying directory names, or even a directory path (as above), we have been using relative paths. When you use a relative path with a command like ls or cd, it tries to find that location from where we are, rather than from the root of the file system.

However, it is possible to specify the absolute path to a directory by including its entire path from the root directory, which is indicated by a leading slash. The leading / tells the computer to follow the path from the root of the file system, so it always refers to exactly one directory, no matter where we are when we run the command.

This allows us to move to our data-shell directory from anywhere on the filesystem (including from inside data). To find the absolute path we're looking for, we can use pwd and then extract the piece we need to move to data-shell.

%%bash2

pwd

%%bash2

cd /home/nbuser/library/data/data-shell/

Don't execute this command, as the absolute path may be different for you! Instead select the output from your pwd command up to and including data-shell.

Run pwd and ls -F to ensure that we're in the directory we expect.

These then, are the basic commands for navigating the filesystem on your computer: pwd, ls and cd. Let's explore some variations on those commands.

What happens if you type cd on its own, without giving a directory?

%%bash2

cd

How can you check what happened? pwd gives us the answer!

%%bash2

pwd

It turns out that cd without an argument will return you to your home directory, which is great if you've gotten lost in your own filesystem.

Nelle's Pipeline: Organizing Files¶

Knowing just this much about files and directories, Nelle is ready to organize the files that the protein assay machine will create. First, she creates a directory called north-pacific-gyre (to remind herself where the data came from). Inside that, she creates a directory called 2012-07-03, which is the date she started processing the samples. She used to use names like conference-paper and revised-results, but she found them hard to understand after a couple of years. (The final straw was when she found herself creating a directory called revised-revised-results-3.)

Each of her physical samples is labelled according to her lab's convention with a unique ten-character ID, such as "NENE01729A". This is what she used in her collection log to record the location, time, depth, and other characteristics of the sample, so she decides to use it as part of each data file's name. Since the assay machine's output is plain text, she will call her files NENE01729A.txt, NENE01812A.txt, and so on. All 1520 files will go into the same directory.

Now in her current directory data-shell, Nelle can see what files she has using the command:

ls north-pacific-gyre/2012-07-03/

This is a lot to type, but she can let the shell do most of the work through what is called tab completion. If she types:

ls nor

and then presses tab (the tab key on her keyboard), the shell automatically completes the directory name for her:

ls north-pacific-gyre/

If she presses tab again, Bash will add 2012-07-03/ to the command, since it's the only possible completion. Pressing tab again does nothing, since there are 19 possibilities; pressing tab twice brings up a list of all the files, and so on. This is called tab completion, and we will see it in many other tools as we go on.