Remotes in GitHub¶

Version control really comes into its own when we begin to collaborate with other people. We already have most of the machinery we need to do this; the only thing missing is to copy changes from one repository to another.

Systems like Git allow us to move work between any two repositories. In practice, though, it’s easiest to use one copy as a central hub, and to keep it on the web rather than on someone’s laptop. Most programmers use hosting services like GitHub, BitBucket or GitLab to hold those master copies; we’ll explore the pros and cons of this in the final section of this lesson.

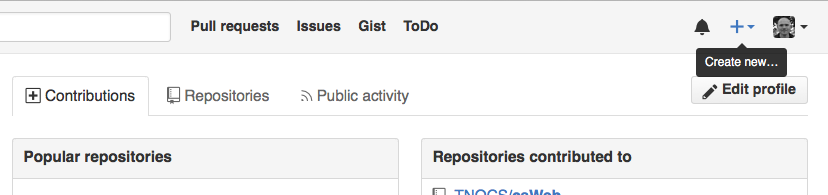

Let’s start by sharing the changes we’ve made to our current project with the world. Log in to GitHub, then click on the icon in the top right corner to create a new repository called planets:

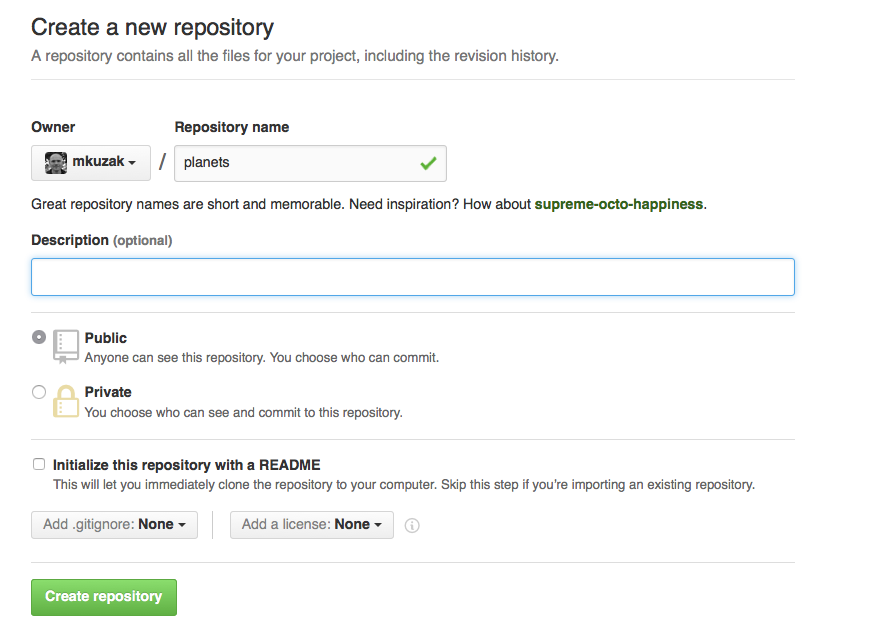

Name your repository planets, add an optional description and the click Create Repository.

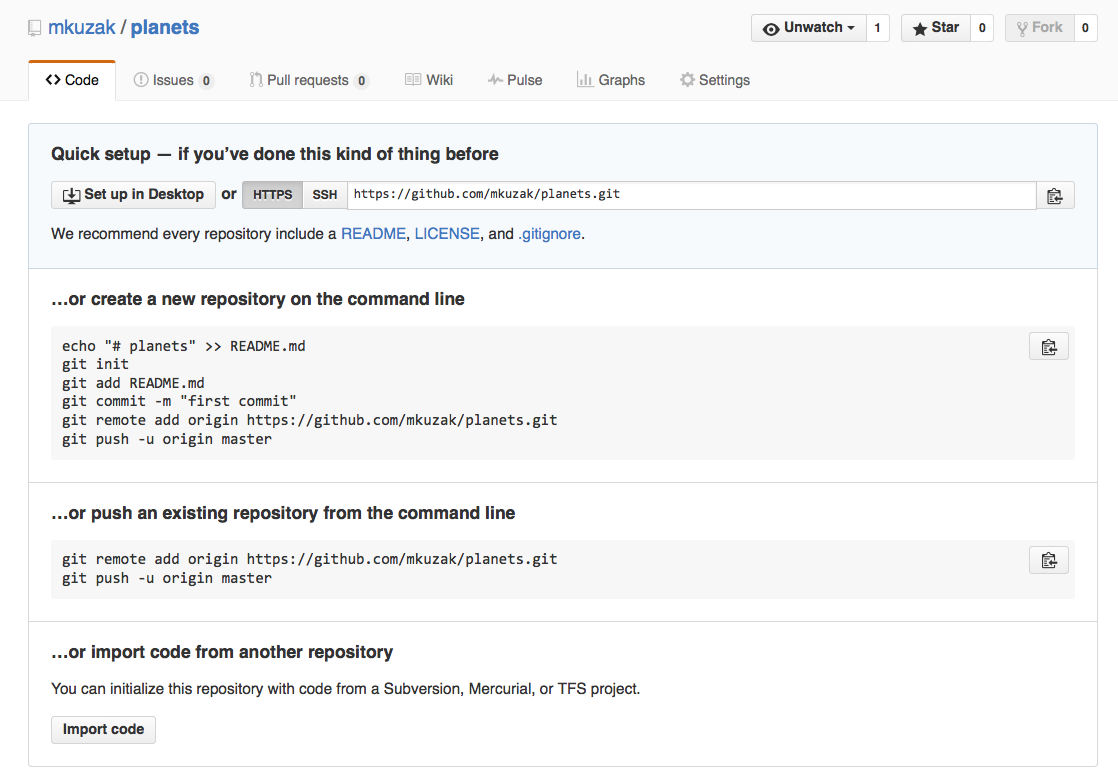

As soon as the repository is created, GitHub displays a page with a URL and some information on how to configure your local repository:

which effectively does the following on GitHub’s servers:

% mkdir planets

% cd planets

% git init

Our local repository contains our earlier work on mars.txt, but the remote repository on GitHub doesn’t contain any files yet:

The next step is to connect the two repositories. We do this by making the GitHub repository a remote for the local repository. The home page of the repository on GitHub includes the string we need to identify it:

Click on the HTTPS link to change the protocol from SSH to HTTPS if needed.

Copy that URL from the browser, go into the local planets repository, and run this command:

% git remote add origin https://github.com/vlad/planets.git

Make sure to use the URL for your repository rather than Vlad’s: the only difference should be your username instead of vlad.

We can check that the command has worked by running git remote -v:

% git remote -v

origin https://github.com/vlad/planets.git (push)

origin https://github.com/vlad/planets.git (fetch)

The name origin is a local nickname for your remote repository. We could use something else if we wanted to, but origin is by far the most common choice.

Once the nickname origin is set up, this command will push the changes from our local repository to the repository on GitHub:

% git push origin master

Counting objects: 9, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (6/6), done.

Writing objects: 100% (9/9), 821 bytes, done.

Total 9 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

To https://github.com/vlad/planets

* [new branch] master -> master

Branch master set up to track remote branch master from origin.

Our local and remote repositories are now in this state:

We can pull changes from the remote repository to the local one as well:

% git pull origin master

From https://github.com/vlad/planets

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Already up-to-date.

Pulling has no effect in this case because the two repositories are already synchronized. If someone else had pushed some changes to the repository on GitHub, though, this command would download them to our local repository.